The dreary season of 2016 is rushing past my ears, sounding like a hummingbird heading for home. I thought there would be time...to reflect, to learn new tools, to come to conclusions regarding practicing practices and troubling tech. Instead, I ran as fast as I could just to stay in same place.

But I promised a few colleagues that I would document '3 before me' - Academic Technology's ode to setting tech limits in Canvas - in time for Winter quarter. Here's '3 before me!' in micro-content form:

The Practice

#1) The course FAQ thread in Discussion Board. Someone will answer it there, often before you, the instructor, even sees it.

#2) The University Help Desk. You're not Tech Support and you don't need to know why their Windows Vista/BB9/IE8 combination doesn't display PDFs correctly. IT is paid to explore those issues, and some of them enjoy working on the problem.

#3) The syllabus. Doh! Time, due date, requirements, process is usually outlined there. If it's about course content issue, they should look there first.

3 before me. Easy rule. Put it in the syllabus and your online teaching becomes easier and your students become less dependent. Scout's honor.

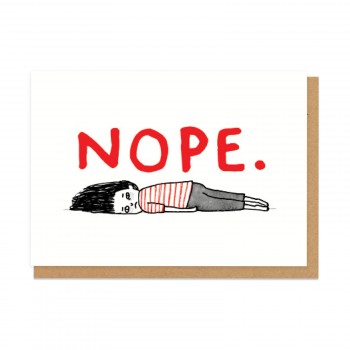

Lots of faculty think they'll be seen as "nice" if they ignore this advice. Do so at your own peril. Online options can grow work at exponential rates when you start obsessing. '3 before me' is especially gold in online teaching. Why?

- so you don't burn out teaching online

- so students take ownership of their learning and problem-solving

- so they form community unto themselves

3 Before Me.